A Crossroads for Turkey

The nation of Turkey sits in a unique position. It sits in both Europe and Asia. It is a democracy which frequently violates the civil liberties of its citizens. It is a NATO member and it maintains close ties with Russia. Its upcoming presidential election, set for May 14, will have large implications for the nation’s future, a turning point toward democracy or autocracy.

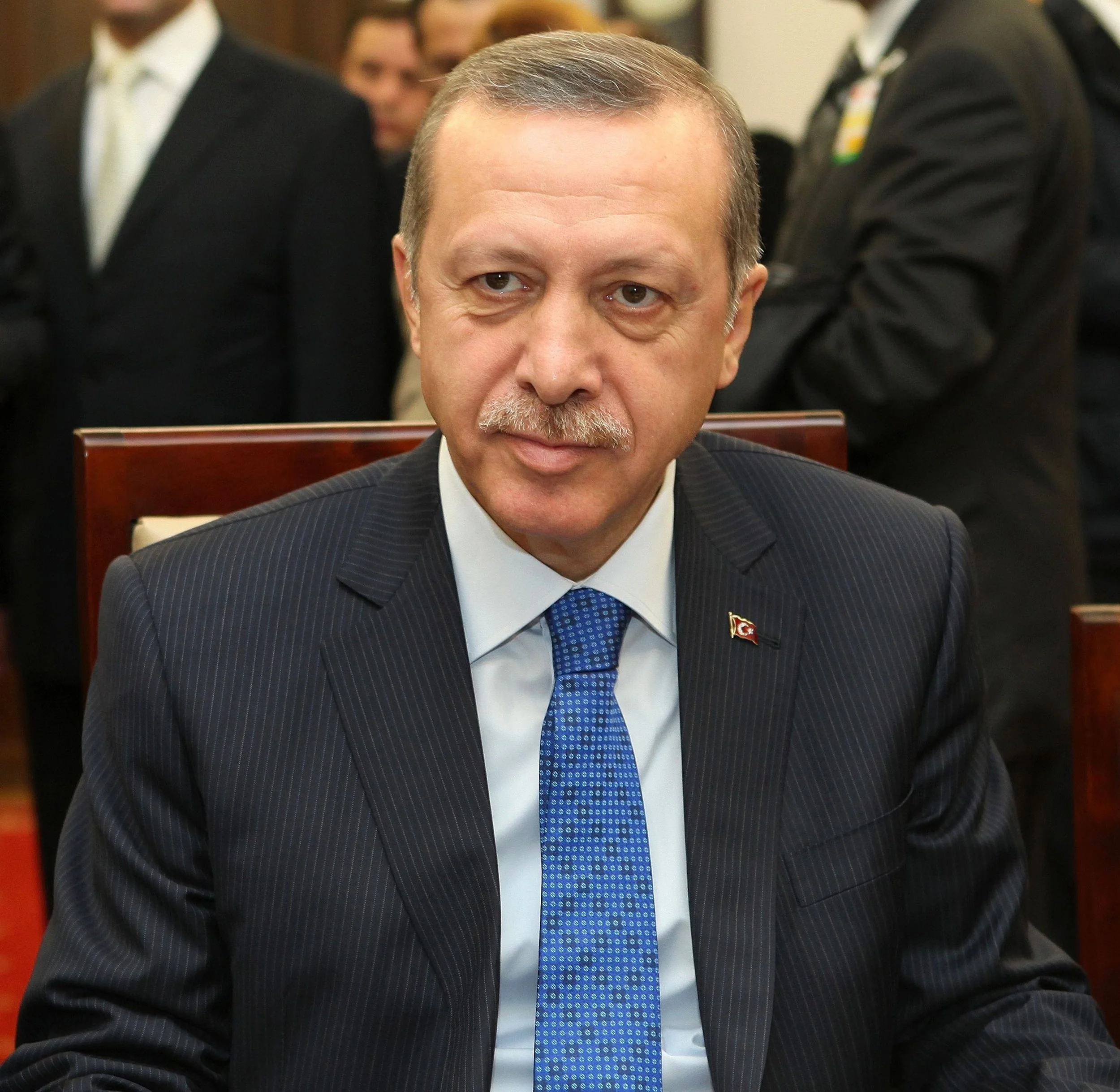

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been Turkey’s head of state for two decades; his Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been in power since 2002. He was Turkey’s prime minister from 2003 until 2014, when he was elected in the country’s first popular presidential elections after weakening the parliamentary system. His tenure has seen accusations of corruption and authoritarianism, decreased secularisation, and a deadly failed coup in 2016.

Since the coup, Erdoğan and the AKP have increasingly cracked down on dissent, with severe restrictions on speech. Turkey is rated as ‘Not Free’ by Freedom House, a non-profit organisation which advocates for democracy and civil liberties, the same rating received by Russia, Iran, and China. It is the world’s leading jailer of journalists, and suppresses social media and internet access, frequently restricting websites including Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter.

Despite government repression, the upcoming election is a legitimate, albeit difficult, opportunity for Erdoğan to be unseated. His disadvantaged opponents cling to their chances to elect a new leader for the nation, perhaps their greatest since 2002. Erdoğan faces a newly challenging situation in the wake of the disastrous earthquake which struck the region in February and with the Turkish economy imperilled by many of his policies.

A few opposition parties have come together, some reluctantly, to back Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the head of the centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP). Polls have put Kılıçdaroğlu ahead of Erdoğan, with the former recently gaining the support of the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), a large and mostly Kurdish voting bloc. Kılıçdaroğlu, nicknamed ‘Gandhi Kemal’ by some of his supporters, promises to restore Turkish democracy and to the Turkish parliament.

Although polls show Kılıçdaroğlu ahead, it will be difficult to unseat Erdoğan. He is a powerful leader, and represents to his supporters the stability which the Turkish government has failed to offer in the past. Additionally, Erdoğan and his allies control significant portions of the nation’s media outlets, offering a chance to sway public opinion. The AKP could also turn to more direct means to influence Turkey’s democracy, as in the case of Ekrem Imamoğlu.

In Istanbul’s 2019 mayoral election, Imamoğlu defeated the AKP candidate in the first round of voting. Erdoğan, unwilling to concede Turkey’s cultural and economic centre, had the results of the election cancelled and called for it to be run again later that year. Again, Imamoğlu was victorious and became mayor of the city, demonstrating the Turkish people’s commitment to democracy. In December 2022, however, Imamoğlu, who had become a popular opposition figure, was sentenced to three years in prison and was banned from holding public office for calling the court which cancelled the vote ‘stupid’, leaving Erdoğan with one less opponent to worry about.

The upcoming election will not be held on a level playing field, but Kılıçdaroğlu and his coalition have a chance. Restoring democracy in Turkey would put it back in position to join the European Union. Erdoğan’s defeat would also mean an end to Turkey’s veto of Finland and Sweden’s bids to join NATO; it would bolster the organisation at a time when NATO protection seems increasingly important, owing to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Erdoğan’s foreign policy has been one contrary to his predecessors; rather than seeking to deepen ties with the west as a NATO member, Erdoğan has embraced interventionism and sought to deepen ties with China and Russia. He desires a powerful, independent, and influential Turkey. In frustration to its NATO allies, Turkey has continued relations with Russia, but recently agreed to cooperate with European and American sanctions, demonstrating the need for continued sanctions on Russia.

May’s election will be a turning point for Turkey. If Erdoğan wins another five-year term as president, perhaps a more likely outcome, he may deepen his hold on the Turkish government and cement himself as a true autocrat. If Kılıçdaroğlu wins and follows through on his promises, NATO will have two new members and Turkey’s quest to join the EU will be resumed. Either way, it is vital that NATO ties with Turkey are maintained. It is a powerful regional ally in Western Asia with influences in the Caucuses, an especially important friend to have in the time of Putin’s expansionist tendencies.

Image of President Erdoğan, courtesy of Michał Józefaciuk via Wikimedia, some rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the wider St. Andrews Foreign Affairs Review team.