Getting a Voice? The Struggle Toward Recognition for Australian Aboriginals

There has been a gradual yet sluggish movement since around the end of WWII for formerly imperialist countries to reconcile with their histories and engage in varying degrees of corrective action for the damage they caused. At least in the western conscience, hallmark examples of such nations include France, the United States, and the United Kingdom, with notable former colonies including Haiti, India, and the Congo. In contrast, Australia, as a settler colony, is seldom considered in similar light to Britain’s former extraction-based colonies; still, it saw its own fair share of atrocities committed against the native population. In 2023, Australia finds itself in a position more akin to its Global North counterparts. The country recently took aim at its latest target for native equality, proposing an amendment to its constitution to ‘alter the Constitution to recognize the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice’. The ‘Voice’ mentioned in the amendment is not an idealist concept but a literal government position which would have been created. The idea was to have a small group of indigenous peoples to represent the interests and will of the broader community within Australia’s parliament.

This proposal was decisively rejected by the Australian population, failing to obtain either of the two necessary majorities to pass. For the amendment to pass it needed both a majority of support in the a majority of Australian states and a majority from the overall voting population. Not a single state produced a majority of support, meaning the proposal fell far from its mark. The ‘No’ voters fell largely into one of three main groups. One was a part of the non-indigenous citizenry that felt the amendment represented a backslide in their own rights or level of freedom. Although the legislation only advocates for the creation of a single Voice for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, some felt this additional measure of representation posed a threat to their own.

A group on the opposite political end that also voted no was a portion of this underprivileged community itself who felt the proposal was an empty gesture meant to distract from the real issues they face. Lidia Thorpe, an Aboriginal Senator summarized this position: ‘This is not our constitution, it was developed in 1901 by a bunch of old white fellas, and now we're asking people to put us in there - no thanks’. Thorpe and like-minded individuals believe the only path towards true equality is a complete overhaul of the Australian constitution.

The third and perhaps most critical group who voted against the new amendment were independents and disconnected voters who were not particularly engaged in the issue on either side. This sect was massively persuaded by the ‘No’ side’s campaign slogan: ‘Don’t know? Vote no’. As votes were going towards changing the foundational document of the Australian government, most independents upheld the status quo and maintained political inertia on the subject.

This overwhelming sentiment demonstrated throughout the nation illustrates how it has not decided how to manage the treatment of the native population. It is important to note that, by almost all metrics of wellbeing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders rank the lowest in socioeconomic status in Australia. Measures focusing on these groups are not aimless but seek to rectify this disparity which is partly due to the colored history of the state.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, a key proponent of holding the referendum, voiced his own disappointment over the result. His platform both on the campaign trail and in office has placed a strong emphasis on fostering a more equitable relationship between Australia’s native and majority populations. In his announcement of the referendum’s results, the prime minister was keen to note how this vote only represented a temporary setback for his platform, yet, vitally, that he respects the citizenry’s decision. This balanced attitude may prove to be the most effective path forward for Australian Aboriginals, as Albanese was able to convince leaders of both the Greens and Lambie party to also support the referendum. Despite ultimately coming up short, there is a hopeful outlook to be gleaned from this rejection. Perhaps future proposals will include more pointed policy that may be able to swing some current dissenters, as the Voice was a very broad and ill-defined governmental body.

Regardless of the margin by which the Voice was rejected, it is undeniable the latest referendum made strides in creating consciousness on the issues facing Australian natives. The opportunity to hear both supportive and dissenting voices speak on the issue allows both sides to better understand one another, and for future policymakers to hone their proposals for a likelier chance at success. Australia is an island with a unique history from much of the colonial West, and hopefully it will further distinguish itself from its Global North peers in its handling of societal inequalities amongst disadvantaged native populations.

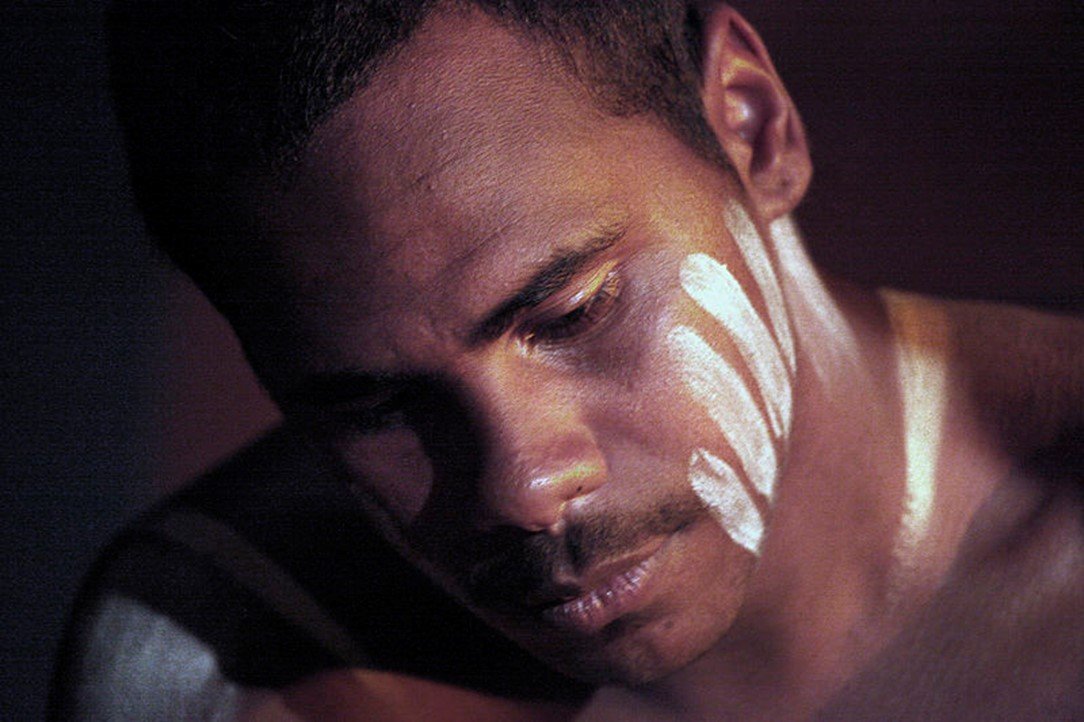

Image courtesy of Steve Evans via Wikimedia, ©2011. Some rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the wider St. Andrews Foreign Affairs Review team.