The History and Future of Democracy in Indices: Introducing The Democracy Index

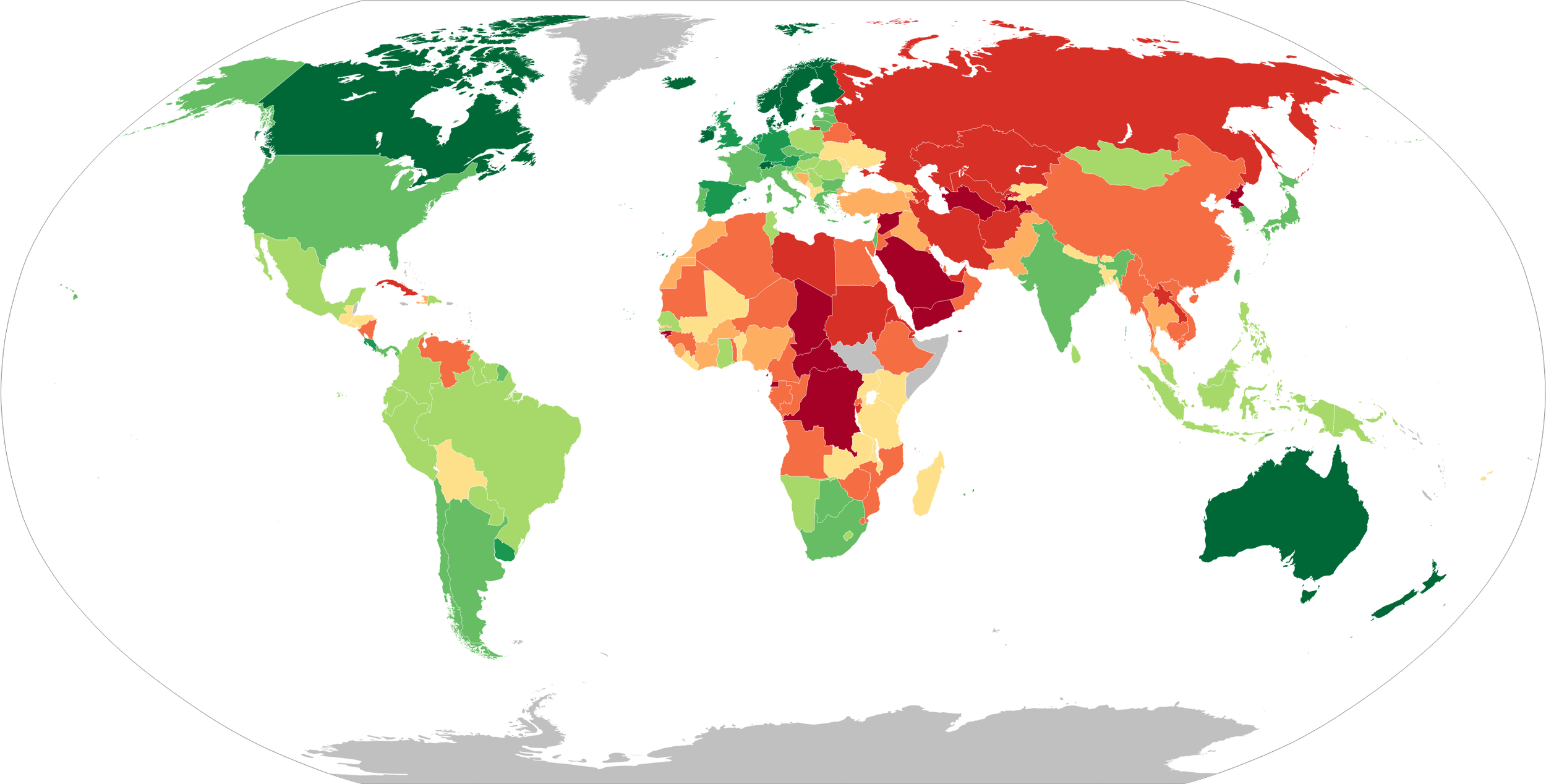

This world map visualises data gathered by the EIU, ranking countries from the most democratic (green) to the least (red). Illustration by Hx7 and obtained courtesy of Wikimedia Commons under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. It’s format has been altered slightly.

Launched fourteen years ago by a sister-company of the London-based newspaper, the Democracy Index’s twelfth edition finds the democratisation of governance on the decrease. The global average is the weakest since the Index was established by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in 2006.

The Democracy Index gathers data on 167 independent states and territories. Scores are taken in five categories: electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties, on a scale of 0-10. States are then grouped according to their overall performance: from full democracies to authoritarian regimes. Norway scored the highest, North Korea the worst.

As the most recent edition from January 2020 shows, less than six per cent of the global population enjoy life under governance worthy of the first label — which contrasts with more than a third who find themselves in the last one. The West’s failure to protect and foster good governance seems to constitute the driving force behind the recent decline.

The sharp regression in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America was unprecedented, whilst a lesser drop was observed in the East and the South of Europe. As a result, for the very first time, the global average score has fallen as down as to 5.44. Currently, the average person lives in a hybrid regime verging on authoritarian rule.

Worrisome trends are to be observed in the purported stronghold of democratic rule. Europe’s eastern borders have not suffered from deterioration yet have seen no improvement since 2006. Poland and Hungary lead the race downward. The 55th and 57th place holders still rank as flawed democracies but the declining independence of the judiciary system and state media ownership project no good perspective. Western Europe, on the other hand, continues its march upward. France and Portugal mark their return to the full democracy club.

The most significant individual contributors to the decline since 2006 are yet far away from the Old Continent. Following Trump’s election, the United States no longer count as a full but rather as a flawed democracy. The biggest decline since the eleventh edition is found, unsurprisingly, in China. Hong Kong, however — and perhaps unexpectedly — still ranks as a flawed democracy.

Major regional trends include the deterioration of the democratic rule in the Middle East. The fruits of the Arab Spring were lost before they matured everywhere except Algeria, a new hybrid regime. Iraq and Palestine moved in the other direction, joining the ranks of other authoritarian regimes.

Positive changes were not a matter of regional tendencies but rather achievements of singular states. None has improved its score more than Thailand which advances now from hybrid regime to flawed democracy. The only non-European country to join full democracies this year is Chile.

Category-wise, the only improvement since 2006 has been found in political participation. Partially responsible for the positive change is the widening global participation in protests and demonstrations. Civil liberty has declined the most, with freedom of speech and media freedom the most glaring losses. Emerging in this new post-truth world are state-owned echo chambers.

What it all seemingly boils down to is the recently coined crisis of democracy — on a global scale. Even 2010 — a year of economic crisis — was not as bad. Democracy is perhaps past its prime; new forms of political participation with the emblematic strong figures of populist leadership auger a sharp turn in how the will of the people is to be perceived and carried out.

The broad white paper report produced by the EIU not only outlines the methodology and findings of the Democracy Index. As for the probable causes of democracy’s recent ill fate, the authors recognise the growing influence of powerful, unelected institutions and bodies. What is yet not stated is whether industry lobbies are hiding behind this umbrella term. An increasing reliance on expert governance behind closed doors has also done its part. What results is the ever-widening gap between the (still democratically-chosen) elites and the national electorate.

Obviously, the Democracy Index has also its weaknesses. It is still young, reflecting only a small part of modern liberal democracy’s lifespan. Yet, what it indubitably succeeds at is illustrating the worldwide erosion of democratic rule. For it surely is a gradual erosion rather than a revolution. The diagnosis of Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt proves accurate: Democracies may die at the hands not of generals, but of elected leaders — presidents or prime ministers who subvert the very process that brought them to power.

Statistics cannot predict what will happen. They can only hint at what follows from current trends. But trends can always be reversed. Joan Hoey, the Democracy Index’s editor, remarks that the recent wave of protest in the developing world and the populist insurgency in the mature democracies show the potential for democratic renewal. So far, however, populism’s golden age has been providing inspiration for more and more politicians worldwide. This casts doubt upon the (albeit dim) optimism of the white paper, unmatched by the report’s findings.