'Where is the EU?' The Reality for Refugees

With the sheer amount of those forcibly displaced from their communities nearing upwards of 70.8 million, the role of such actors – refugees, internally displaced persons, and asylum seekers – on global politics cannot be ignored. The rate in which people flee their communities in hopes of seeking safer grounds has increased at an alarming rate. As a result, political elites in other states are forced to deal with the rising ‘refugee problem’ by formulating policy approaches to migration control. Most notably under pressure to provide humanitarian assistance in the form of reception and support for asylum seekers are the member states of the European Union. However, while the EU continually boosts its position in humanitarian aid operations in regard to asylum seekers, why has the EU – rather than create safe pathways for their reception – taken security precautions to prevent their arrival?

The failure of EU member states to act in accordance with their humanitarian goals is most visibly highlighted in the wake of the tragic fire that consumed Europe’s largest refugee camp, Camp Moria, off the Greek coast. Notwithstanding the fires that have left nearly 13,000 men, women and children without proper shelter or access to basic services, Camp Moria had already been a point of contestation. Built to house 2,757 migrants yet forced to fit 12,767 – mainly women and children – Camp Moria was extremely overcrowded; providing inadequate conditions with limited access to food, water, sanitation and health care. When asked about the inhumane conditions of the camp, one Syrian refugee interviewed in the aftermath of the fires pleaded that their family had ‘lost everything in Syria, we came looking for safety, this is not safety.’ What happened to make the island of Lesvos, and more specifically Camp Moria, the European Guantanamo Bay?

During its height in 2015, the refugee crisis saw nearly one million irregular migrants flee war-torn communities and seek asylum in the safety of Europe. During this time, media dominated by tragic imagery of mass drownings in the Aegean Sea and families stuck at overcrowded border control checkpoints on the Greek Islands put pressure on European countries to act – and act fast. However, nervous the crisis would pose a ‘major threat to the soul of Europe’ and undermine Euro-centric culture, a worry voiced by Italian Foreign Minister Paolo Gentiloni, the EU struggled to cope with the influx. Scrambling for a resolution to the consistent stream of asylum seekers, the EU enacted many short-term fixes, one being the EU-Turkey deal – an extension of the EU ‘hotspot approach’.

A statement of cooperation between the EU and the Turkish government, the deal sought to control the migration of asylum seekers from Turkey to the Greek Islands while providing a safe and legal route to the EU. Greatly beneficial for EU member states, the deal greatly externalized their borders, allowing Greece to return all ‘irregular migrants’ to Turkey. Defined within the EU- Turkey deal, irregular migrants are those deemed unable to gain asylum status and/or those who have travelled through a safe country where they could have claimed protection upon entry. Under the terms of this deal Turkey, the country many asylum seekers pass through so to get to Europe, is defined as a safe country. This condition in the deal allows the EU to adopt the policy of returning asylum seekers, putting further distance between Europe and those seeking its safety.

While successful in its aim to reduce the flow of refugees with the number of irregular arrivals dropping by 97%, the EU-Turkey deal continually boosted by the EU commission raises serious ethical and legal implications. The deal at its core fails to protect due to its underlying objective’s lacking any sense of protective measures and rather seeking border control via ‘burden-shifting’. Following the deal, the responsibility of reception has fallen greatly on Greece. What many asylum seekers were hoping to be a passageway to safety became their final destination as they wait in camps for claims of asylum status to be processed. With Greece’s system under such burden, coupled with the reluctance for EU support, the conditions of camps such as Moria have deteriorated to the point that one man described it to be ‘a grave for humans. It is hell’.

While unclear in its origin, the three separate fires that devastated Camp Moria have brought to light the failure of the EU’s ‘hotspot approach’ to asylum reception. Being called upon by nongovernmental groups like the Human Rights Watch to establish permanent pathways of sharing the responsibility for receiving and processing asylum applications, the EU has paid a shocking lack of attention to the building pressures that lie at the front line of the ‘refugee problem.’ Demonstrated by the signing of the EU-Turkey deal, the EU has put in place structures to ‘burden-shift’ the responsibility, thereby limiting the influx of refugees. This tactical move by wealthier EU member states is a dangerous and irresponsible act of self-interest that devolves an inordinate amount of power to the individual state while putting weaker EU member states at disproportionate strain.

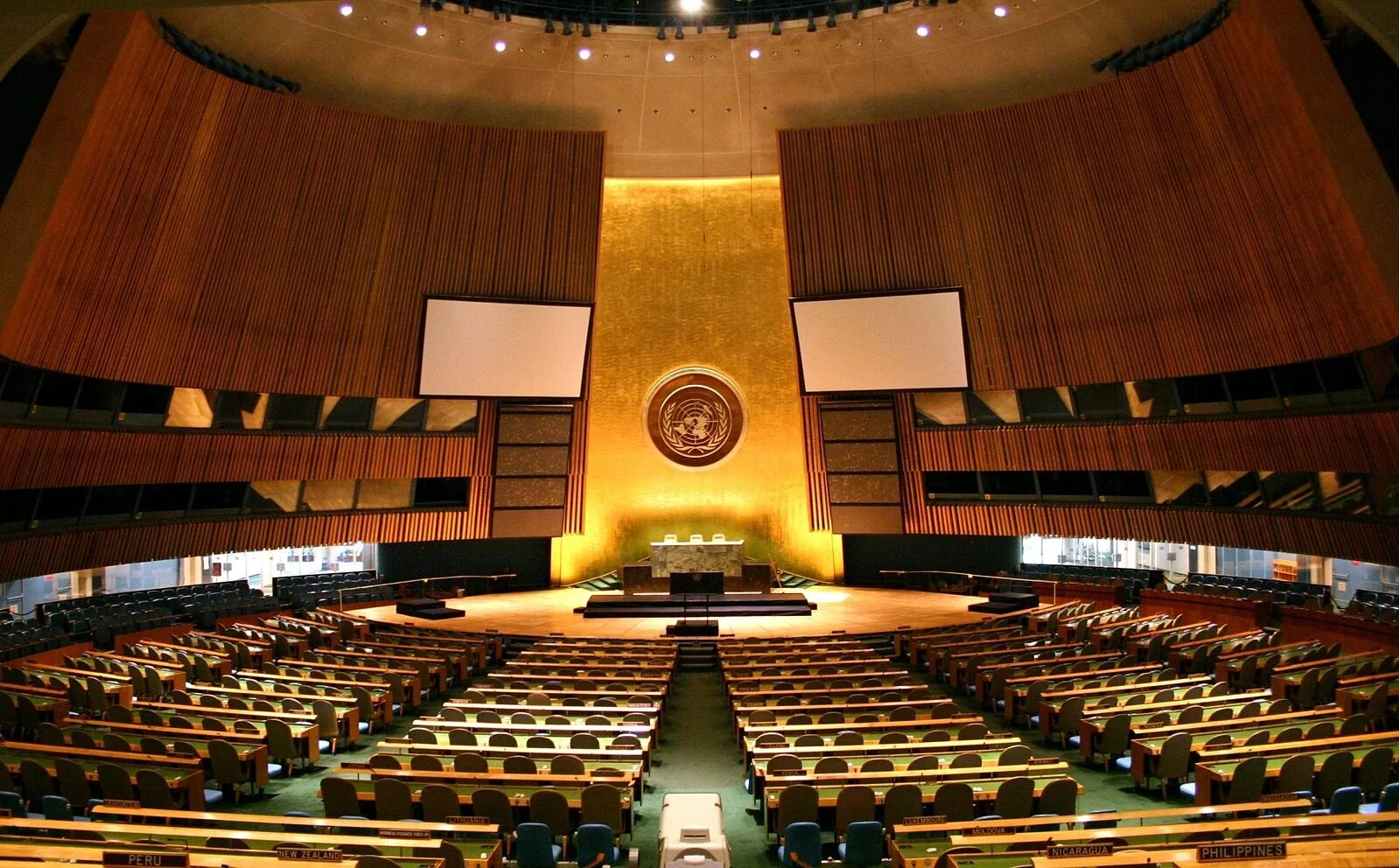

Image courtesy of Georgios Giannopoulos via Wikimedia, ©2015, some rights reserved.